Submitted as part of University of Toronto’s ARC1036 final essay coursework on April 21st 2010.

You can download the PDF with citations, images and bibliography here.

When thinking about sublime architecture the beautiful picturesque English gardens and the prisons of Piranesi are the first works that come to mind. Combining the historical monumentality of these kinds of works with the mutability and chaos of post-modernism creates an uncanny concept - one which is hard to grasp based on simple semantics. The multitude of philosophy, literature, art and architectural theories and concepts produced to oppose strict modernist formalism, were seminal in allowing a modern re-interpretation of the sublime in the early seventies. The uncanny feeling of the term „post-modern sublime‟ is therefore a reaction to the combination of two very familiar concepts into one unfamiliar idea. It is interesting to note that the post-modern sublime was a combination of two concepts as well. The classic sublime worked by conveying terror or beauty through visual stimuli. The post-modern sublime tries to transmit similar concepts – however the means through which it does so are different, relying on the invisible micro-processes of chaos embedded into the idea of entropy. The post-modern sublime will therefore be explored in relation to entropy while at the same time investigated under the original ideas embedded into the sublime and the picturesque sublime. Robert Smithson’s multitude of works provides a great practical explanation of the post-modern sublime. It is important to note how despite working with different categories of art and architecture, entropy was seminal to Smithson in most of his designs. The essay will therefore be an attempt to understand how the artist treated entropy so that it became a new kind of sublime which when integrated into landscape had long-lasting effects on art and architecture.

The similarities and differences of the classical sublime and the post-modern sublime are important in understanding the new post-modernist interpretation of the concept in the seventies. The sublime was understood both as being in awe at beauty or being in awe at a terrifying vision while at the same time not being directly affected by it. The picturesque British gardens illustrate the former instance, while Piranesi’s Carceri are an interpretation of the latter one. The picturesque sublime revolves around the arrangement of staged art.¹ It is an attempt to create something sublimely beautiful and natural looking from a meticulously controlled environment.² The concept of the picturesque and its relation to the sublime was something which resurfaced in the post-modern debates of the late sixties and therefore was nothing new to Smithson. Graziani goes as far as considering Smithson’s work as a historically conscious detour through the category of the picturesque sublime.³ Piranesi’s work on the Carceri on the other hand conveys the characteristic ruination and a fantastic sublime which was born out of terror and scale.⁴ Smithson is able to inherit the specific element of awe from both concepts and unify it to his reinterpretation of the sublime. The Spiral Jetty for example is both a massive staged landscape as well as an illustration of the entropic processes of nature.

The post-modern sublime inherits the shock, but rather than connecting it to visual astonishment, it conveys an awe of hidden process and entropy. Post-modernism was a movement which grew as a challenge to formalism and the static determinism of modernism. It was therefore based upon concepts of irregularity, mutability and chaos. All three concepts seem natural metaphors of some of Smithson’s works which helps in understanding how the artist conceived his own art. Bargellesi explains the reinterpretation of chaos by Smithson and in doing so places it in the post-modern timeline:

“There is nothing more tentative than an established order. What we take to be the most concrete or solid often turns into a concatenation of the unexpected. Any order can be reordered. What seems to be without order, often turns out to be highly ordered.”⁵

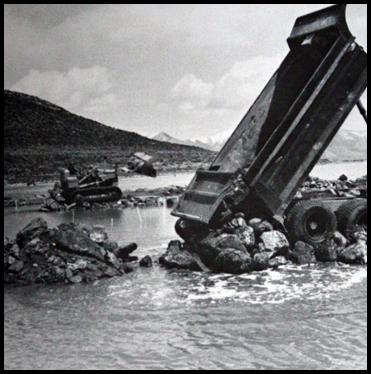

What also helps Smithson in evidencing order from irregularity is the importance of process and decay in his art. His land art is a continuous work in progress which constantly changes in order to compromise with its environment. Decay and time are therefore seminal elements of his work. This is obvious in most of his work which falls into the category of land art. The Spiral Jetty would be the perfect example because of the heightened importance given to the concept of process.⁶ It is also an instance of a work which when viewed from a historical perspective best illustrates these ideas. Sensitive prominence was given to documenting the process of the creation of the Spiral Jetty. Smithson wanted to make the creative process part of the final artwork and therefore reveal an often hidden element of art - especially in the face of entropy and continuous process in the specific site.⁷ Furthermore because of its placement in an unprotected environment, the Spiral Jetty was expected to constantly change. The erosion processes pertinent to decay and entropy would be revealed with the passing of time on the very fabric of the Spiral Jetty. By choosing a lake which was red because of the thriving bacteria and algae – beyond creating an analogy with blood and life’s primordial beginnings⁸ - Smithson evidenced the invisible processes of change within the lake itself. He placed a work which demonstrated entropy even in its counterclockwise whirl⁹ into an environment which was naturally entropic. Smithson wanted to collaborate with entropy. In a society which saw chaos as destruction he was attracted by the possibility of process and reversal.¹⁰ Time, in function of process, is therefore an important element in understanding how the concept of entropy was developed and integrated into the artist’s work. It also illustrates the idea of a new sublime which combined a staged yet mutable environment to the scary invisibility of process in the creation of post-modern sublime.

Beyond his interest in the intervention of human kind on nature and the effects of our species on the environment¹¹, Smithson was clearly interested in immortalizing time in a number of his works. Film was an obvious example used in The Spiral Jetty, however photography and mirrors are even more prominent displays of his fascination with time. Time in his mirror and photographic works however is also analyzed as an individual element, not strictly connected to process as in the Spiral Jetty. Smithson explores the ephemerality of time and documents his attempts to capture it through photography and reflection. His Cayuga Salt Mine Project begins as an example of a double-photographic piece.¹² The artist photographs the reflections of the site on mirrors. He conceives of these images as photography of reality and time. One can feel and capture time much more efficiently by immortalizing a “live reflection” – showing the physical mirror as a frame of reference as well as the reflection contained within the mirror - rather than the actual site. Smithson describes the process by explaining how his idea of time is better contained within the mirror:

“I’m using a mirror because the mirror in a sense is both the physical mirror and the reflection: the mirror as a concept and abstraction; then the mirror as a fact within the mirror of the concept. The mirror is a displacement, as an abstraction absorbing, reflecting the site in a very physical way.”¹³

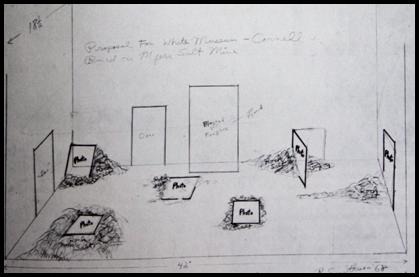

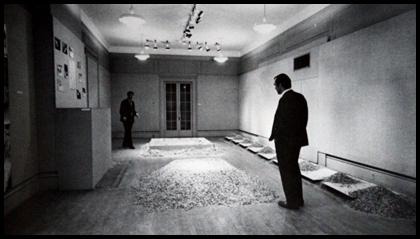

Smithson therefore tries to contain time within the temporality of the reflection. Interestingly enough he does not leave the mirrors on site. He takes them with him and displays them within the gallery as if the ephemeral reflections from the original site still survive within the physical mirror.¹⁴ In his mind the mirror hasn’t completely disclosed itself until it is exposed in the gallery with the multitude of other elements.¹⁵ By virtue of their reflective properties the mirrors were more appropriate than the pictures because of their ability to convey a more immediate and live aspect of time within the walls of the gallery.¹⁶ The illusions contained within the mirror and the hidden properties of time are used by Smithson as actual materials of creating art.¹⁷ By trying to capture something so elusive the artist is giving another re-interpretation of sublime art. An artistic post-modern sublime which when understood correctly is arguably more terrifying than the graphical terror of Piranesi’s sketches.

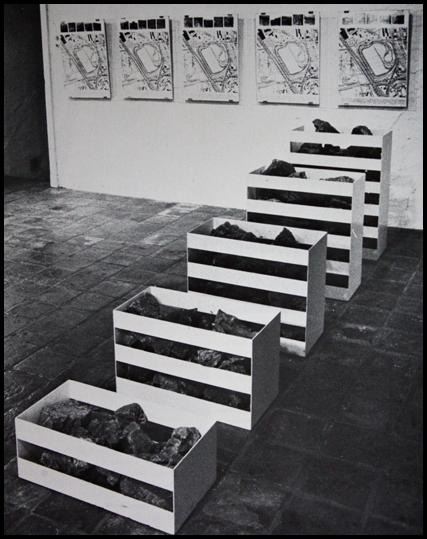

The final element which seems seminal in understanding Smithson’s work resides within the non-site: the artist’s need to unveil the invisible. This idea looks like an attempt to reveal what has hence been covered by the invisibility created by too much visibility. All the obvious elements of the site are hidden allowing what is invisible in the actual site to be exposed in the non-site – in the process, involving both entities in dialectic through the use of documents, indexes and samples¹⁸. In some cases these elements have been concealed forever – in other cases they have been hidden by modernism. Smithson does not distinguish between the two – he treats the process of revelation identically in his artwork. The Pine Barrens non-site is similar - in its attempt to reveal what is hidden - to the Oberhausen non-site, despite the ideological and meaningful difference between the two sites. The modernist hidden impurities of the industrial processes in Oberhausen are equal to the dirt buried under the multitude of small pines in the Pine Barrens non-site. The Oberhausen non-site however is the best example for its distinctive revealing qualities while exposing how Smithson imagines balance in all of his sites. His nonsites serve as the fringe yin of the yang represented by the actual sites: the two complementing one another and therefore completing the expression of the whole site facilitated by Smithson. The Oberhausen was conceived after Smithson visited the heavily industrial Ruhr District in Germany.¹⁹ It was a response to the modernism induced industrial production he witnessed at the site. As all non-sites it served as:

“…a reconfigured “window” that is both vertical and horizontal, more a map than a picture, more material than visual, more diagrammatic than pictorial, and > as architectural as it is sculptural.”²⁰

The distinctive feature of this specific non-site was its direct intended affront to modernism and industrial production. The bin/rock relationship was reversed and the produced served as a container, while impurities gained the status of the contained. Smithson therefore reinterpreted the idea of production by reversing the value of elements in the Oberhausen non-site. Smithson was extremely interested in the impurities created by process as evidenced above in the essay. Impurities in this specific non-site therefore take control of the artwork becoming the driving force in evaluating the site through its waste by-product.²¹ Smithson mingled the impurities with the geological features and industrial processes of the site through the presence of maps and photography.²² According to Smithson revealing the impurities was seminal in being able to expose the truth of every site/non-site relationship. The non-sites are therefore able to reveal the whole range of site visibility from the minuteness of rock fragments to the large topographical maps.²³ With what Bargellesi calls “anti-vision” the unconsolidated and hidden micro-processes of every site were revealed by Smithson in creating yet another instance of awe and surprise illustrating the post-modernist sublime.

Conclusively it is evident that Smithson treated entropy in a multitude of ways and in the process created out of it a new kind of sublime which – while inheriting a number of elements from the original idea of the sublime – had an unmistakable effect not only on the site but on the ideas and theories of contemporary landscape art and architecture. A combination of the importance of entropy, process and time as well as the attempt to reveal the hidden elements of the site are witness to the success of reinterpreting the notion of the sublime from a postmodernist perspective. The complement given by the different categories of Smithson’s work are also helpful in arguing holistically rather than focusing on a singular category of his work. It is furthermore plainly noticeable that the thought processes, theories and ideas initially entertained by Smithson had a lasting effect not only on abstract art but also on landscape architecture in general. The artist was seminal in developing and illustrating the confusing theoretical ideas of postmodernism into palpable artworks while contributing to giving post-modern landscape theory a much-needed direction.

Footnotes

¹ Graziani, p.427

² Ibid, p.427

³ Graziani p.428

⁴ Graziani, p.430

⁵ Bargellesi, p.121

⁶ Graziani, p.433

⁷ Hobbs, p.197

⁸ Ibid, p.197

⁹ Ibid, p.197

¹⁰ Barghellesi, p.177

¹¹ Bargellesi, p.13

¹² Hobbs, p.132

¹³ Hobbs, p.133

¹⁴ Hobbs, p.133

¹⁵ Bargellesi, p.109

¹⁶ Hobbs, p.132

¹⁷ Bargellesi, p.111

¹⁸ Linder, p.12

¹⁹ Hobbs, p.114

²⁰ Linder, p.12

²¹ Hobbs, p.115

²² Graziani, p.433

²³ Graziani, p.441

Bibliography

Bargellesi, Guglielmo. Robert Smithson Slideworks. Verona: Carlo Frua. 1997. Print.

Graziani, Ron. Robert Smithson‟s Picturable Situation: Blasted Landscapes from the 1960s. Critical Inquiry, Vol. 20, No. 3 (Spring, 1994), pp.419-451. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1343864

Hobbs, Robert. Robert Smithson: Sculpture. London: Cornell University Press. 1981. Print

Lee, Pamela M. Chronophobia: On Time in the Art of the 1960s. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2004. Print.

Linder, Mark. Towards „A New Type of Building‟: Robert Smithson‟s Architectural Criticism. In Robert Smithson ex. cat. MOCA LA (Berkeley: UCP, 2004).