This week I share snippets of the most interesting ideas on economic growth I have encountered in the past year as part of my ongoing research on the urban circular economy. This issue is 1800 words long & it should take 6 minutes to read through; hope you enjoy it!

Humanity today is like a waking dreamer, caught between the fantasies of sleep and the chaos of the real world. The mind seeks but cannot find the precise place and hour. We have created a Star Wars civilization, with Stone Age emotions, medieval institutions, and godlike technology. We thrash about. We are terribly confused by the mere fact of our existence, and a danger to ourselves and to the rest of life. —E. O. Wilson

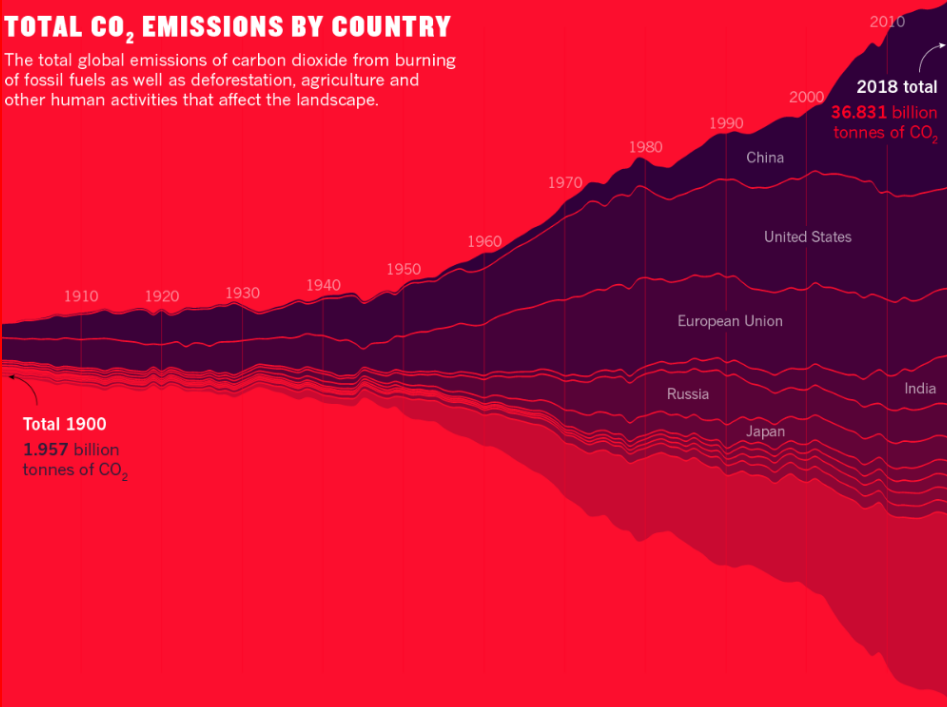

Total CO² emissions by Country

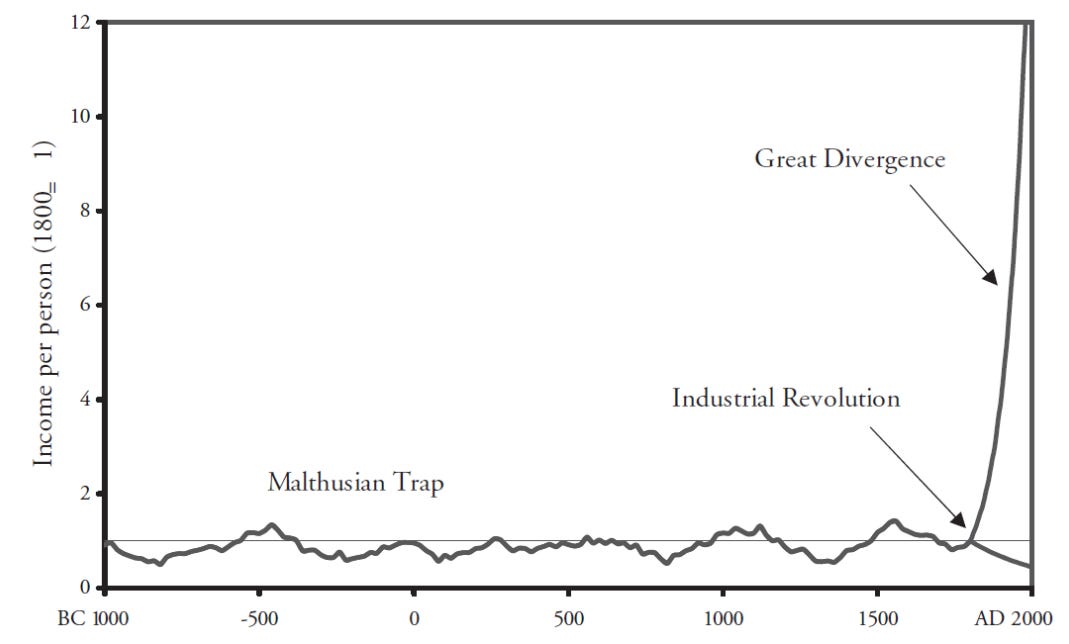

In 1798, a decade after the famine that contributed to sparking the French Revolution, Thomas Malthus proposed the concept of what is now known as the Malthusian Catastrophe. In it, the English economist put forth that population grows exponentially, while food production grows arithmetically; civilization would therefore reach breaking points and population would need to respond to the constrains of famine: “Famine seems to be the last, the most dreadful resource of nature. The power of population is so superior to the power of the earth to produce subsistence for man, that premature death must in some shape or other visit the human race.”

Gregory Clark, A Farewell to Alms

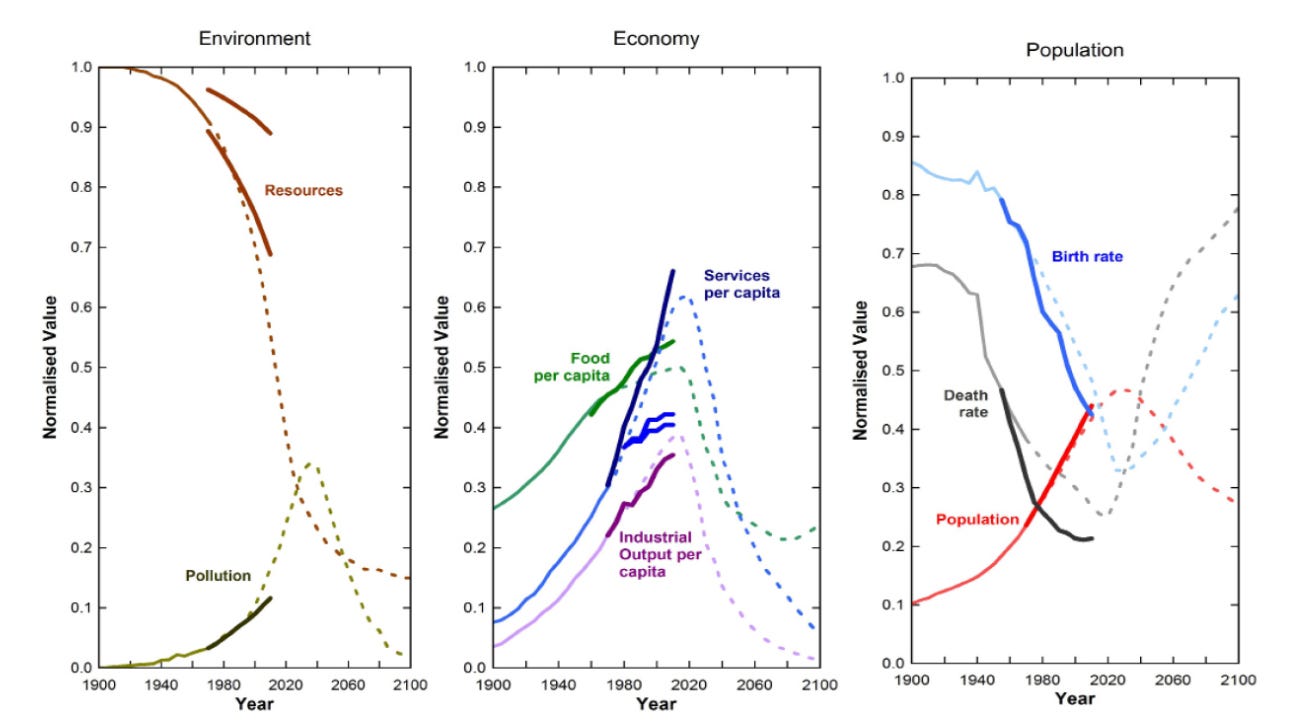

In the summer of 1970 the Club of Rome - an ephemeral multi-disciplinary group of individuals - echoed a more pragmatic revision of Malthus in The Limits of Growth; interestingly the report was backed by one of the first computer simulations on the future of the global economy. Despite moving in and out of favor since it’s publication, sustainability is still broadly assessed on the five basic tenets used in that report: population increase, agricultural production, nonrenewable resource depletion, industrial output, and pollution generation. The conclusion of the report argued for a future of self-imposed limitations, where man “can live indefinitely on earth if he imposes limits on himself and his production of material goods to achieve a state of global equilibrium.” The report is complex and controversial but the projections from one of the proposed scenarios have tracked fairly well with real-world performance .

Limits to Growth BAU scenario vs. data to 2010 from Is global collapse imminent

The modern economy has seemingly broken the pessimist trend of Malthus and the Club of Rome by relying upon a form of sustained open-ended growth thanks to constant cycles of innovation. Every time economic development approaches a ceiling, human ingenuity finds ways to innovate around it, breaking the Malthusian trap and pushing its consequences to the next generations. As described in Scale however exponential growth is unsustainable in a finite setting and in the long term always leads to a finite time singularity. The real discussion revolves around whether we are approaching that breaking point in the short-term future or our generation can push the problem forward once again.

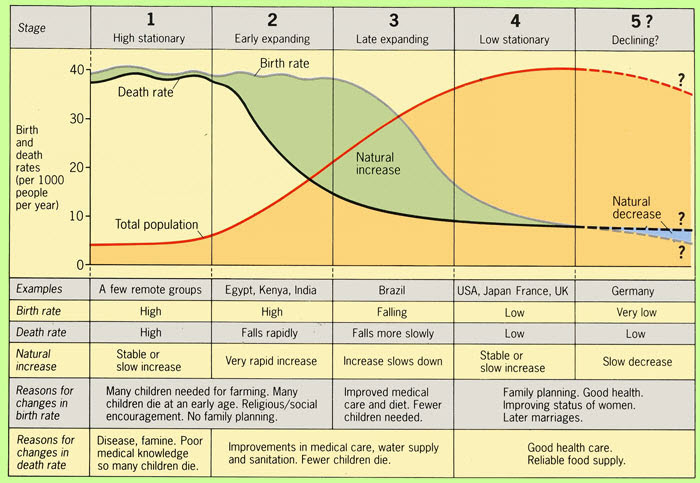

Demographic Transition Model by Warren Thompson

Some developed countries - having reached demographic transition - now exhibit minimal population growth & rapid aging: prosperous economies estimate negative or nil population growth by 2050. Material demand can therefore be expected to remain stable, especially considering the continuous improvement in energy efficiency. Stabilization in affluent economies still leaves us with the immense and possibly insurmountable challenge of the developing world, with the Asian and African transition at the forefront. Until their standard of living approaches western ones, global material consumption growth rates will be difficult to neutralize. We will face decades of huge demand for energy and commodities in developing economies; barring natural catastrophes or prolonged economic downturns it is unlikely that new material extraction will be reduced or kept at current levels. Most estimates forecast an increased demand of materials to 2050 even in low or moderate economic growth scenarios. The issue is exacerbated by Jevons’ paradox, more commonly known as rebound effects which I have touched upon before in the context of urban mobility.In similar fashion to how organisms accumulate drug resistance after being continuously exposed to it - human systems seem to build consumption resistance the more efficient resource-use becomes.

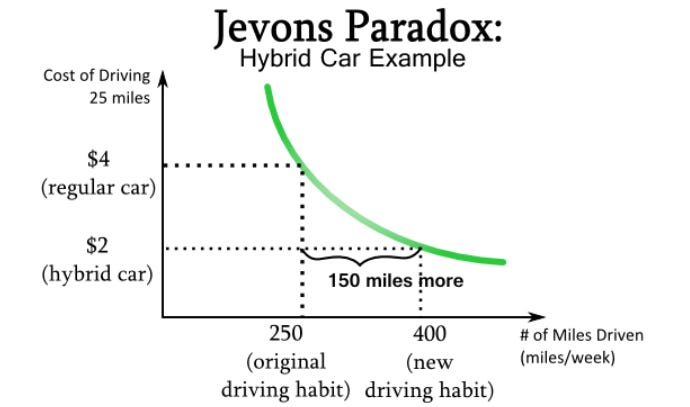

Jevons’ Paradox illustrated through hybrid car fuel savings by Didactic Discourse

Jevons’ paradox has kept per capita consumption high despite increased efficiency. The nineteenth-century economist William Stanely Jevons remarked that increased system or energy efficiency does not necessarily lead to less total consumption. This has been clearly illustrated last century: despite electrical appliances becoming more efficient, total electrical energy consumption per capita has increased even in developed countries. The persistently falling cost of electricity has counterintuitively affected behavior. While the expectation would be that households would consume less energy when more efficient appliances would become available, this is often not the case. Instead of accumulating in savings, a reduced cost of consumption per unit often translates to an increased number of units consumed: households keep their appliances on for longer or buy more of them. It is therefore important to underline that increased efficiency does not necessarily lead to less consumption. Looking at the future however it is foreseeable that once a region achieves a certain standard of development it might be possible to maintain quality of life while slowing material consumption; if innovation keeps it’s current pace in the future it might even be possible to break Jevon’s paradox and achieve zero growth, or even degrowth. Various researchers have argued in favor of confronting our culture of consumption and embracing a more local and autarkic logic of development.Wicked problems like confronting exponential growth are best approached through a fragmented set of different measures, like a bout of chemotherapy; attacking the exponential growth of cancerous cells through different strategies with a cocktail of drugs sometimes chokes off the disease.

In approaching strategies of slow growth, zero growth or degrowth we need to be careful in framing them within the context of our fragile political systems. Here communication and populism become part of the picture again - too often utopias are wielded as short-term political weapons. Degrowth does however point to a calmer, more local lifestyle; it is in fact a philosophy of living more than an economic strategy. Victor provides a similar framework of slow growth terming it sustainable prosperity; it interestingly addresses inequality and labor just as much as environmental issues. From an urban perspective, Leipzig among other cities of the former German Democratic Republic has straightforwardly dealt with its slow decline by proactively demolishing more than 20,000 vacant residential units and replacing them with green space; in doing so it cut the cost of services as well as removing a constant eyesore that had an impact on the perception of Leipzig’s urban fabric. Similar strategies have been adopted in Youngstown, Ohio and Detroit, Michigan: demolishing vacant buildings will not make people come back, but it might help in keeping existing inhabitants from leaving.

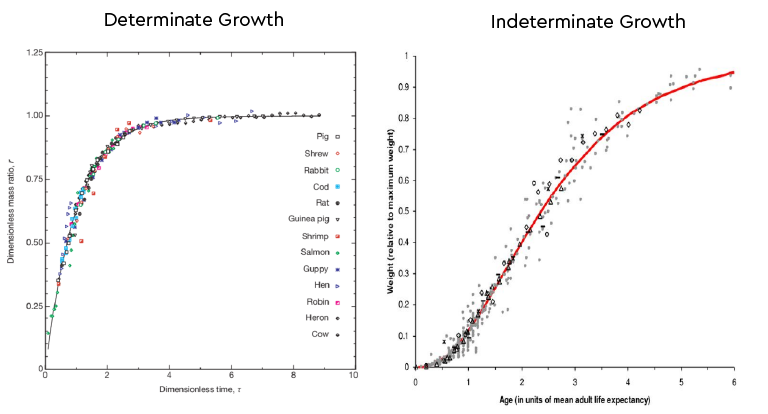

Determinate Growth (West et al.) vs Indeterminate Growth (Froese)

In discussing the future growth of economies it might be important to make an analogous connection to biological systems. It is interesting how all animals have a similar growth curve that biologists term determinate growth. The energy they devote to growth slowly approaches zero and, at a certain point in time - when the animal has matured - all of its energies go toward maintaining a steady state. A similar pattern was previously illustrated by the demographic transition model: as nations become more developed, birth rates fall and populations stabilize. In some singular cases populations might also slowly shrink, probably driving towards a lower baseline equilibrium. It is therefore possible to foresee how the global economy might stabilize by itself once it reaches a certain scale. It is unclear whether as a civilization we will be able to attain that developmental steady state or we will destroy ourselves before we achieve it. There is another risk however - our economies might follow the growth pattern of fish or trees which is termed indeterminate growth. This dreadful alternative looks suspiciously like a finite time singularity; our economy might be growing to its death.

Ultimately despite there being fixed limits to the impact that wealth can bring to human well-being, it is politically impossible to imagine a leader who promises citizens less, or at best, as much as we have today. No one is willing to promise change which might generate negative or stable growth even though researches at Princeton have long figured out that the impact of income on happiness tapers off at $75,000 a year. Change, just as growth, has become a constant of western political culture; it is similarly a counterintuitive concept. We want sustainability but also the comforts that come with unsustainable development. There is nothing wrong with this form of growth, except that we do not know whether it can accommodate the population of the whole planet. Chants of change are common in political rallies worldwide, but implementing change in our own local lifestyles is a litmus test of integrity; it demonstrates whether we really mean it, beyond the social signaling associated with sustainability.

Did you like this issue of thinkthinkthink? Consider sharing it with your network: Share

📚 One Book

Nothing Is True and Everything Is Possible: The Surreal Heart of the New Russia by Peter Pomerantsev

Nothing is True and Everything is Possible - that killer title is an epitome of our current times. This one is a good book that stems from the author employment at different Russian media companies. It quickly evolves into all kinds of segues on the surrealism of transition in Russia and - from our current perspective - even the world at large. It reminded me of Adam Curtis’ HyperNormalisation, a prescient documentary on our current state of affairs.

📝 Three Links

Uncertain Times by Jessica Flack and Melanie Mitchell\ A fantastic post-mortem of 2020 through the lens of complexity.

Welcome to the Government-IT Infrastructure Complex by Albert Venger\ Tech defragmentation and the imminent need to distribute & federate.

Makoko Floating School, beacon of hope for the Lagos ‘waterworld’ by Jessica Collins\ Innovation happens at the boundaries: the floating school of Lagos’ largest slum.

🐤 Five Tweets

Crypto Twitter presages the

— balajis.com (@balajis) January 11, 2021

2030s.

Pseudonymity and big personalities, economic alignment and crypto tribalism, distributed cooperation and hostile forks, and above all a moral, technological, and economic case to replace legacy institutions with internet-native alternatives. https://t.co/059gONHafe

A murmuration of starlings. pic.twitter.com/Q4F6SFptji

— Sierra Club (@SierraClub) October 10, 2020

DALL-E — our new neural network for generating images from text:https://t.co/HMGw12LPDd pic.twitter.com/XEnUJOGsc6

— Greg Brockman (@gdb) January 5, 2021

I’m going to write about my friend who built this brewery in his barn. He’s my sort of person. Has his own little value system he lives by. He also built something really amazing. Not just the system, but the network of people who run it. pic.twitter.com/ZJ6zvUYZLy

— Tim 💯 (@HundredthIdiot) January 9, 2021

Architectural fantasy and social idealism: 'Historical Monument of the American Republic' (1867–1888) by Erastus Salisbury Field pic.twitter.com/qUW0GqSieb

— Federico Italiano (@FedeItaliano76) January 7, 2021

This was the seventeenth issue of thinkthinkthink - a periodic newsletter by Joni Baboci on cities, science and complexity. If you really liked it why not subscribe?