This issue on urban accretion is 850 words long & it takes ~3 minutes to read; enjoy it!

“In the 1950s, when Jane Jacobs fought against running a road through Washington Square Park, she was fighting to save nineteenth-century sprawl from twentieth-century sprawl.” - Ed Glaeser

Cities are incremental. They gain complexity through a slow and iterative process of accretion. Charles Lindblom first delved on the topic of incrementalism in his seminal 1959 paper on public administration “The Science of “Muddling Through””. In his future work Lindblom termed the process of incremental changes driving systems disjointed incrementalism. These are small iterative changes that slowly improve the process in the medium and long term and are typically unbound by large-scale formal strategies or plans. Lindblom argued that such changes are more appropriate to the way we typically work: we muddle through, we deal with what’s more important first and review our priorities daily, depending on a context of perpetual shifting conditions.

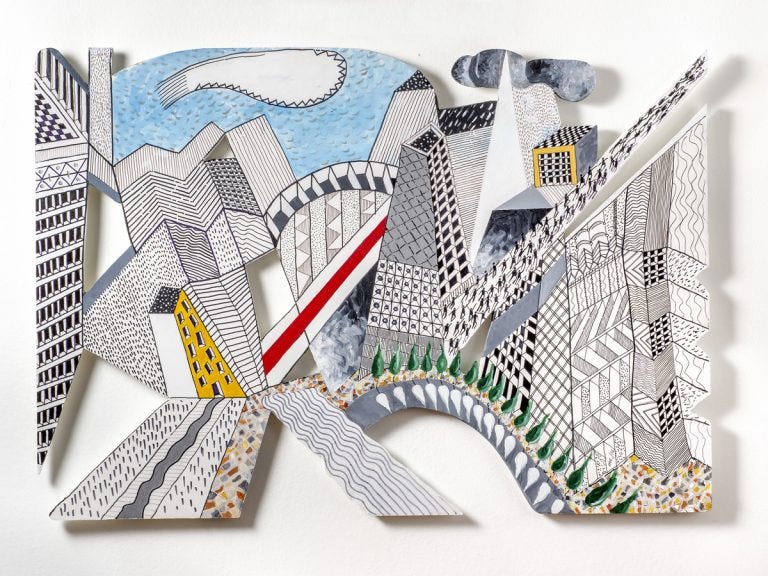

The disjointed incrementalism series by artist/architect/planner Marios Camhis

In social terms Matthew Desmond also addresses the importance of incrementalism in his magnum opus on eviction. He describes how communities of neighbors who cooperate and share trust can improve their streets and make them safer and more prosperous. Small daily interactions help build trust over time. There’s no overarching plan and no guarantee of success. Rather there are good odds that will favor positive outcomes in the community. This approach may be very successful at the community scale, but it is often disturbed by the real-world: land markets, housing commodification, or supply and demand. These networks are rarely resilient in that they take a long time to form but can be unraveled fairly quickly.

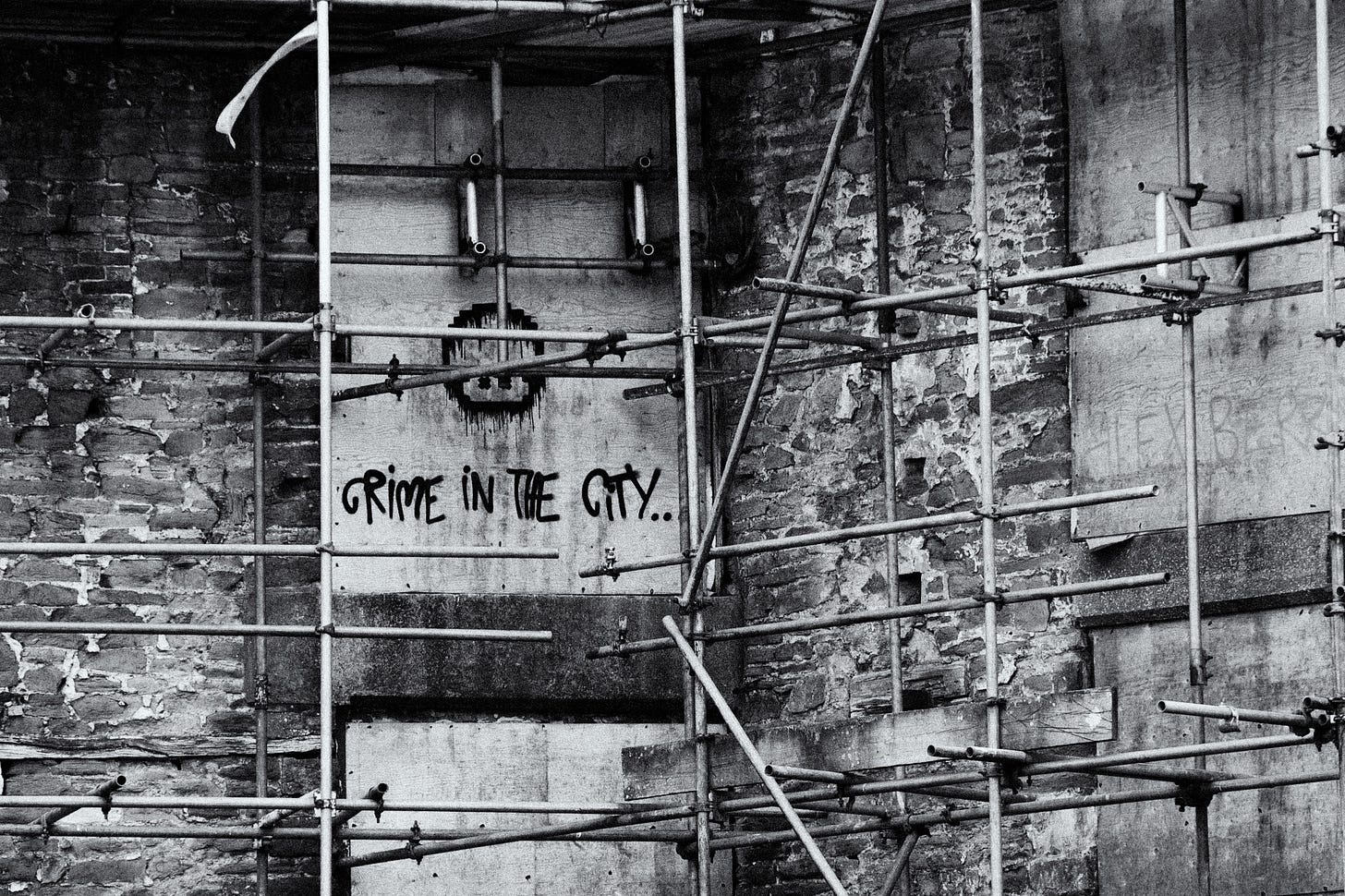

Urban accretion generates character. The slow collection of dust and defects makes places feel original. New buildings lack grit - they need time to settle in our psyches, time to accumulate wrinkles in their skin. We can’t stand cracks on our phone screens but subconsciously yearn for cracks in our public realm. DC’s waterfront attempts to emulate a more traditional architecture in its public space by employing conservative materials and design. It’s way more successful than similar bland modernist projects but still lacks the grit, the history that typically characterizes traditional materials.

Bristol by Tash Jones

Harking back to disjointed incrementalism, cities need both new buildings that start building character for the future as well as old buildings that are well established and aged from the past. This disjointed model of development allows the urban fabric to change through parallel engines and provides a constant rate of urban revitalization.

Haussmann’s Paris plays a dual role in the argument of disjointed incrementalism: on one hand it has been built by demolishing - between 1853 and 1870 - more than half of the existing buildings of Paris; on the other hand it stands today as one of the most aesthetic and elegant examples of 150 year-old planning and development. The urban unification of central Paris stands as a formal product of Haussmann, a single decisionmaker rather than a disjointed model of development. As Glaeser puts it: “Haussmann did, in fact, destroy a city to save it.” Paris’ model of development however is the exception that proves the rule; further it’s a plainly unsustainable model which is impossible to emulate in our current paradigm.

Étoile area as redesigned by Haussmann by DigitalGlobe/Rex

Successful cities are able to digest and metabolize incremental change. Really successful cities are even able to welcome change and constantly absorb it. Christopher Alexander describes how the urban patterns of his pattern language emerge organically and gradually of their own accord: “every act of building, large or small, takes on the responsibility for gradually shaping its small corner of the world to make these larger patterns appear there.” This emergent and resilient approach to change is also evident in our attempts to make architecture waterproof. It is typically extremely difficult, costly and a high-maintenance endeavor to keep a house 100% waterproof. More intelligent techniques employ materials that can easily absorb and release moisture with little long-term consequences. Ultimately this quote of Harvey I also mentioned a couple of months ago in the context of emergence comes to mind: “No alternative to the contemporary form of globalization will be delivered to us from on high. It will have to come from within multiple local spaces - urban spaces in particular - conjoining into a broader movement.”

Did you like this issue of thinkthinkthink? Consider sharing it with your network: Share

📚 One Book

Remembrance of Earth’s Past trilogy by Liu Cixin

I have been enjoying this tedious, extremely long but also mind-expanding sci-fi trilogy by Liu Cixin. It’s one of the few sci-fi sagas I have encountered which manages to capture and describe the vastness of space. Further by skipping eras, the author is able to imagine a plausible future of human civilization’s transition into an interstellar space age. Character development is severely lacking and there’s lots of skippable fluff, but at the same time the ideas that Cixin ping-pongs around the book are fascinating. Read it with lots of freedom to skip sections you feel aren’t up to par with advancing the story. Trust your instincts, they really aren’t.

📝 Three Links

Transforming Tirana by Vanessa Norwood\ I speak with Vanessa Norwood on Tirana & the power of distributed planning.

Why is it so dark in outer space by Kenny Hemphill\ Brief historical exploration on why outer space is dark.

Wind Map by Fernanda Viégas and Martin Wattenberg\ A live visualization of the movement and speed of wind.

🐤 Five Tweets

Neural networks are systems for reducing information: from pixel luminosities to shapes to objects to obstacles.

— Mathieu Hélie (@mathieuhelie) January 25, 2021

Our nervous system attempts to reduce information to help us make decisions. Some of it may be reduced in excess, which is why psychedelic therapies show promise.

As geographic fragmentation costs fall, both a theory and empirical analysis show that concentration and regional specialization fall for sectors and rise for occupations , from Antoine Gervais, James R. Markusen, and Anthony J. Venables https://t.co/yrAAdS1SKc pic.twitter.com/uXFbJJ7Jqo

— NBER (@nberpubs) January 23, 2021

When capitalism gets depression pic.twitter.com/j1yczELgNy

— senior vice president of jerks (@rajandelman) January 23, 2021

In 2003 Adam Nieman created this image, illustrating the volume of the world’s oceans and atmosphere (if the air were all at sea-level density) by rendering them as spheres sitting next to the Earth instead of spread out over its surface https://t.co/7sJXBwUgk5 pic.twitter.com/hes6XQNO3b

— Massimo (@Rainmaker1973) August 16, 2019

Something fascinating about Twitter: used well it's an immensely powerful tool to think with. But if you look at the mentions of someone famous or powerful you'll see it's hard for them to benefit in this way. It's a rare technology where power actually denies or inhibits access.

— Michael Nielsen (@michael_nielsen) January 24, 2021

This was the nineteenth issue of thinkthinkthink - a periodic newsletter by Joni Baboci on cities, science and complexity. If you really liked it why not subscribe?