How’s your Tuesday going urban enthusiasts? The past five weeks of the newsletter were a brief foray into some of the most defining characteristics of complex systems from the perspective of cities: emergence, resilience, self-similarity, feedback loops, and lever points. I will keep the series going but for now let’s jump back to the typical modus operandi; here’s a few ideas on urban inequality.

From an economic standpoint cities and urban regions account for 85% of global GDP. It is only logical that cities are magnets of poverty. They offer the best chances of improving one’s self. The world’s economy resides in cities; urbanization is closely correlated to development. I tend to think of cities as social and economic generators: they churn prosperity.

The Bangladeshi arrival city of London may be portrayed, with some truth, as a place of crime, religious extremism, and ill health, but it has also functioned for its second generation as a great integration machine. The London-born Bangladeshis, the children of the curry-house owners and sweatshop workers, have marched into the center of British society. They perform better in school than less concentrated immigrant groups and considerably better than the local white English population. There are now as many Bangladeshi Britons departing Tower Hamlets for middle-class districts of London each year as there are arriving from Sylheti villages. This neighborhood, in other words, is a functioning integration machine. - Doug Sanders¹

Social Inequality as seen from the sky with by Johnny Miller

Despite a highly unequal distribution of wealth, cities have lifted hundreds of millions of people from poverty. In a certain sense, transient poverty - especially in emerging cities - is a self-fulfilling prophecy: cities that offer more opportunities become more attractive to those looking to better themselves; ultimately these cities might seem poorer in the process despite being very successful places. From this perspective, urban poverty should not be measured by the volume of poverty but rather by their track record of helping people move up the economic ladder. Glaeser gives an extreme example of a city’s ability to change the fortunes of individuals. He tells the story of one of the most famous families in US politics, the Kennedys:

In 1888, this son of a poor immigrant rose high enough to give a speech at the Democratic national convention. His growing wealth enabled him to send his bright son, Joseph, to Harvard. Patrick Kennedy’s political connections made it natural that his son would marry the beautiful daughter of Boston’s mayor John F. “Honey Fitz” Fitzgerald. Joe Kennedy started out working for the government as a bank examiner, then took over a bank in which his father had substantial holdings. He made a fortune on Wall Street in the 1920s, by more and less savory means. Just as important, he got out in time and found other lucrative pursuits, like investing in real estate and importing British liquor. His sons, of course, became America’s great political dynasty.²

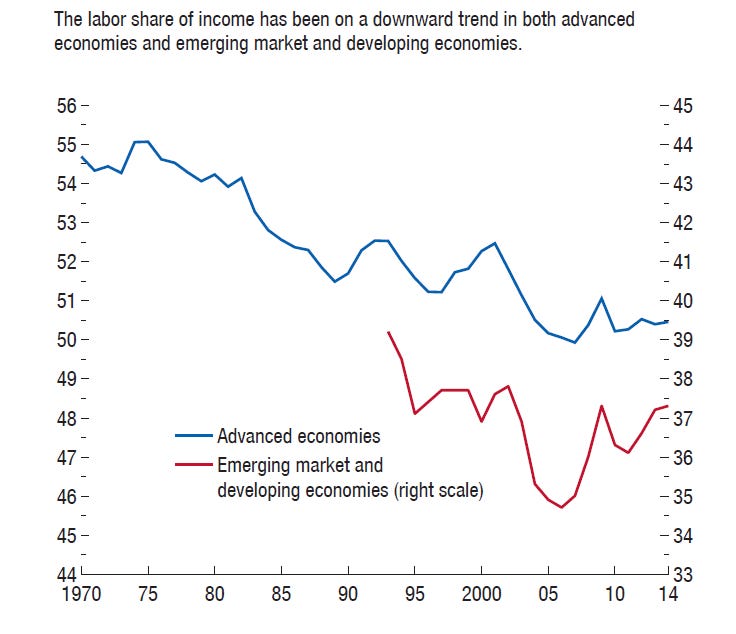

Another feature of emerging cities is their inherent capacity to curtail long-term inequality through growth. Piketty describes how in high-growth populations and high-growth economies, the power of accumulated wealth is gradually eroded. Through inflation, taxation and generational fragmentation, the power wielded by the super-rich in the medium term is balanced by growth. In low-growth scenarios however the opposite is true. Stagnant or shrinking economies put a premium on accumulated wealth and allow inequalities to carry on undisturbed. This phenomenon has been exacerbated by the decreasing share of national income going to labor in the past thirty years; the amount of national income that is distributed through wages rather than capital. Inequality in the US is back to levels not seen since the 1920s. In the post war boom, 99% of wealth went to the bottom 99% of the population, while between 2009 and 2012, 95% of wealth went to the top 1%. The growth-ambiguous perspective of the next decades should take into account not just the exponential population growth of cities but also the general inequality exacerbated by low- or no-growth scenarios.

IMF illustration of the decreasing share of national income going to labor.

The constant discourse on high inequality in cities sometimes camouflages an even larger inequality. In the EU interregional inequality represents more than 70% of the total inequality. That means that inequalities within member states are more consequential than inequalities between member states. From an urban perspective this is one of the reason that despite inequality, cities often vote together: the political differences between the richest of the rich and the urban poorest of the poor, are sometimes narrower than the differences between urban and non-urban dwellers. Andrés Rodríguez-Pose has thoroughly explored the political outlook on inequality in different countries in what he terms “the revenge of places that don’t matter.

You can ignore some of the people some of the time... but if the economy marginalises the most vulnerable, then those who live in the places that seemingly don’t matter take their revenge.#placesthatdontmatter on @Renegade_Inchttps://t.co/1ecgJOaoQGhttps://t.co/YdRNwR8Ala

— Andrés Rodríguez-Pose (@rodriguez_pose) August 18, 2020

¹ Doug Saunders, Arrival City, Location 539\ ² Edward Glaeser, Triumph of the City, Location 1357

Did you like this issue of thinkthinkthink? Consider sharing it with your network: Share

One Book

Arrival City: The Final Migration and Our Next World by Doug Saunders\ Arrival City is a fantastic adventure into informality, slums and arrival. Informal development - which has briefly featured in thinkthinkthink - is a phenomenon which seems unique, yet it is one of the most ubiquitous hyperlocal developments happening in cities worldwide; most importantly it has the potential to raise hundreds of millions out of poverty and reshape cities. The book is a compilation of arrival stories spanning the breadth of 21st century urban epicenters. Highly useful in understanding the changes that will undoubtedly happen to emerging cities in the next thirty years, as well as contemplating the actions we could take today to catalyze a healthier transition for urban newcomers around the world.

Three Links

The Social life of Forests by Ferris Jabr\ The arboreal mycelial network.

Using the homeless to guard empty houses by Francesca Mari\ Residential real estate “innovation”.

The apps keeping Rio’s residents safe from stray bullets by Raphael Tsavkko Garcia\ On tech & favelas in Rio.

Five Tweets

The Chelsea Embankment from across the Thames. Variety in a pattern none of the buildings are the same, but it's a harmonious composition because they all share the same architectural language.

— Robert Kwolek (@RobertKwolek) November 26, 2020

And they're 5-7 storeys tall.

I'm lucky to see this sight almost every evening. pic.twitter.com/4x2CBUqwNz

Can’t get this stat out of my head today

— Garry Tan (@garrytan) December 1, 2020

A million seconds is 11.5 days.

A billion seconds is 31.7 years.

How Biology and living cells "compute", where proteins act like logical gates inside of a cell, giving an example of programming "hello world" using cells. Great talk by Joe.

— Reza Zadeh (@Reza_Zadeh) May 15, 2020

Full video: https://t.co/FoKrsYWRlg pic.twitter.com/nz4ewCPFlE

The paywall on this Economist piece on Foucault as a business guru gives a decent visual expression to the experience of hearing a madman pass you by in the street, only for his voice to fade away as you move on with your day. pic.twitter.com/Z5i76yl3kv

— Anton Jäger (@AntonJaegermm) December 4, 2020

Since when was it necessary for neighborhoods to explicitly advertise their exclusionary zoning practice on the street? What’s going on here? pic.twitter.com/YoUHXHhEbK

— Kasey Klimes (@KaseyKlimes) November 27, 2020

This was the twelfth issue of thinkthinkthink - a periodic newsletter by Joni Baboci on cities, science and complexity. If you really liked it why not subscribe?